Liberty's Birds #1: Bluebird

by Denniele Bohannon

This year's applique Block-of-the-Month series features the diary of Sara T.D. Robinson written her first year in Kansas where she and her husband came from Massachusetts to fight slavery. Kansas; Its Interior and Exterior Life. A Full View of Its Settlement, Political History, Social Life, Climate, Soil, Productions, Scenery, Etc. was published in 1856.

Look for 9 free patterns on the last day of months March to December in 2025.

Kansas Museum of History

Sara Tappan Doolittle Lawrence Robinson (1827-1911)

about the time she moved to Kansas in the mid 1850s

Our houses on the edge of the ridge.

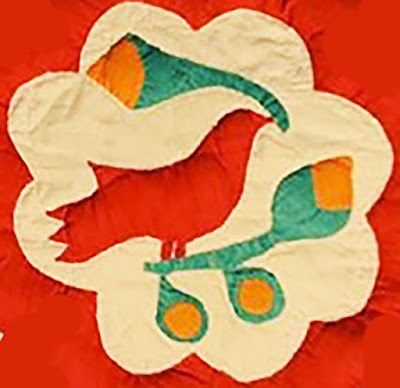

Bluebird by Elsie Ridgely

Emily Jane Hunt (1839-1921) came from Massachusetts.

Sara referred to her younger friend as "E." in the diary.

One major difference: I live in a comfortable '70s modern house; Sara lived in a primitive construction project---a frame house being built around her. Also living in the house, she mentioned a "family" of 5---husband Charles, friend Emily Hunt and a Mr. W. the "elderly" handyman working on the house and keeping the women company when Charles traveled, which was often. When Charles was home visitors came to talk politics with him and frequently spent the night.

Food and building supplies were at a premium. Note the lack of trees on the hill. The woods across the river on the Delaware Tribe's land were full of cottonwood and other trees unsuitable for lumber.

Bluebird by Becky Collis

Sara from a well-to-do Massachusetts family was not one to complain. Easterners would pity us....

Eastern Bluebird

Eastern (not Western) Bluebirds are one of our spring joys, the

same birds that delighted Sara.

Bluebird by Susannah Pangelinan

The Block

The inspiration applique---looks 20th century

Cattle on the hill overlooking Lawrence, Sara's view

https://civilwarquilts.blogspot.com/2025/01/2025s-applique-block-of-month-starts-in.html

And read Sara's book online here:

.jpg)

.jpg)

.webp)